Migratory fish in the River Leven

The River Leven in Fife has been heavily impacted by its long industrial heritage. Past use of the river had previously led to periods of extremely poor water quality, resulting from the sewage and wastewater that was deposited directly into it.

Fortunately, we don’t use the river in the same way nowadays, but this historical legacy still has direct impact on the river today, and to the fish that call it home.

During the industrial revolution, many mills diverted the water out of the river by building weirs across the channel. Many of these old barriers remain today, including a sluice gate that controls the water level in Loch Leven, making it extremely difficult for migrating fish to make it all the way up the river to the loch.

Despite this, many species of fish continue to live in the river, and some even thrive! Salmon, trout, lamprey and eels are regularly recorded within the River Leven, but if they were able to get further up the river, there would be many more fish living within it.

Salmon and sea trout life cycle

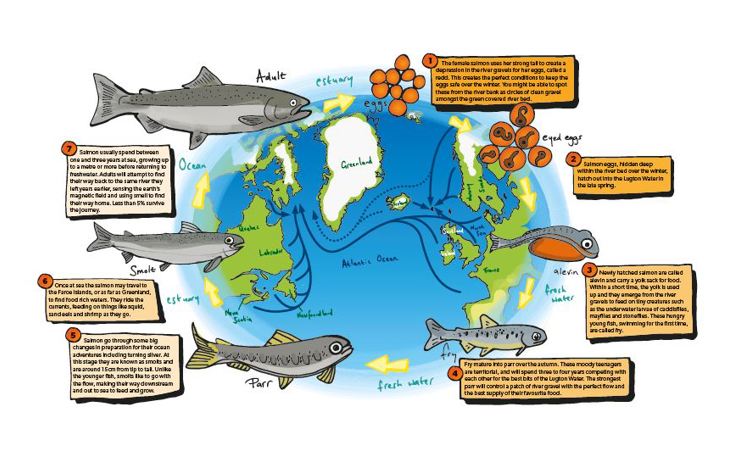

Salmon and sea trout that are born in the River Leven will spend their early life in it. Spawning female salmon produce several thousand eggs, which are laid under gravel in the river. Eggs that are not well hidden may be eaten by predators, such as otters and eels. Eggs can also be smothered by silts, caused by erosion of the river banks.

The luckiest eggs that land in amongst the gravel, will hatch into alevins – small fry with a yolk sac attached. The alevins will remain within the gravel where they are safer from predators, until their yolk sac is empty. The young fry must then swim up into the water to feed, where they are very vulnerable to other river life. The young will spread out and defend a small feeding area on the riverbed.

A year after they are born, the young fish, now known as ‘parr’ will have developed characteristic thumbprints or ‘parr marks’ along their sides.

During the late spring, two or three years after being hatched, salmon and sea trout turn into ‘smolts’. This is a physiological change that will enable them to migrate out to sea and withstand the change in salinity (increase in the saltiness of the water).

Adult salmon and sea trout may spend one or more years at sea feeding and growing before returning back to their the river where they hatched to spawn and start a new cycle of life.

The spawning process is so physically demanding for salmon that their body reserves are severely depleted, and most salmon die soon afterwards. However, a few may recover to become ‘mended kelts’, migrating back out to sea and returning to breed the following year. A larger proportion of sea trout recover and these may continue to migrate between rivers and sea and breed for several years.

Click on diagram to view as larger image.

Lamprey

Lamprey can be found in the River Leven and are primitive fish that don’t have a jaw bone and instead have a large sucker which it uses to latch onto its prey. They used to be known as “Stone Suckers” as they can strongly attach themselves to rocks.

These fish resemble eels more than salmonid fish as they have a long thin body, no scales or bones, and a single nostril. Instead of gills, they have seven open holes on each side behind their head.

Juvenile lamprey are born blind and prefer slow flowing parts of the River Leven where they burrow into the silty parts of the river bed.